In April 1782, Moses Van Campen having been captured by Seneca Indians at Bald Eagle Creek, PA (his life spared through the secrecy of Horatio Jones), forced to run the gauntlet, delivered into the hands of the British at Fort Niagara under the command of Colonel John Butler, and refusing to abandon the American cause and join the ranks of the British, is placed on a vessel bound for Montreal and a British prison. He is thankful for not being delivered back to the Seneca who have plans to torture and kill him having learned his identity.

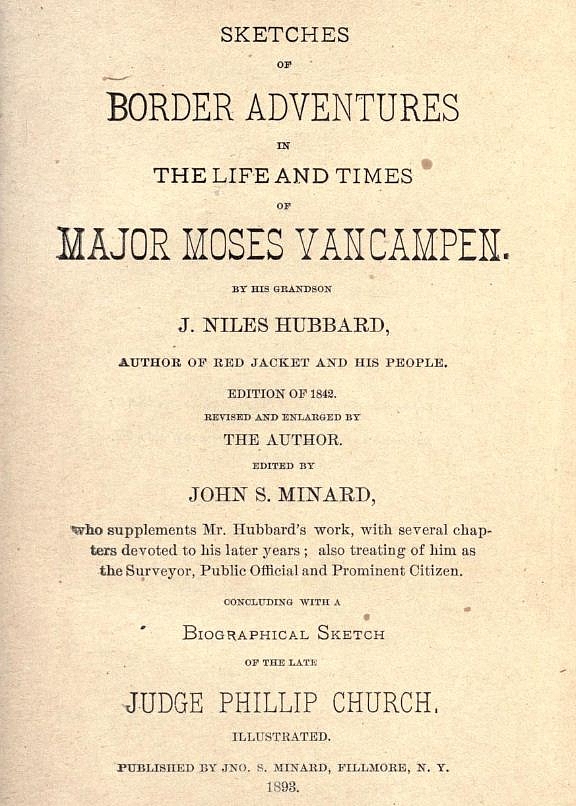

The story of Moses Van Campen celebrating the Fourth of July while a prisoner of war is told in John Niles Hubbard and John Stearns Minard's, Sketches of Border Adventures, In The Life and Times of Major Moses Van Campen, A Surviving Soldier of the Revolution, published in 1893. It shared below.

Continuation of the year 1782—Van Campen is adopted into the family of Colonel Butler—The Indians make a discovery—Seek to obtain possession of him—He is sent to Montreal—Scenes in prison—Sent to New York, and returns to his friends on parole.

Arriving at Montreal he was ushered into the presence of about forty of his countrymen, who were, like himself, prisoners. They were assembled in what was called the guard-house, a large building some seventy or eighty feet in length, and about thirty or forty in width, and was appropriated to the use of the prisoners and of British soldiers, who had them in charge. Within the dark walls of a prison, shut out from the light of day, only as it came struggling through iron grates, Van Campen found a company of men possessing spirits congenial with his own, and he soon formed an acquaintance which from a similarity of fortunes, ripened into the warmest attachment. There were men here from several of the different States, some of whom had been taken, like himself, by the Indians, in their sudden and wary attacks upon the border settlements. Van Campen's coming among them was regarded with no little interest; all gathered around the new prisoner to learn the story of his capture.

They did not, however, surrender themselves to the ill-bodings of despair. The success of their country's arms inspired them with hope, and led them with joy to think of the day as not far distant, when the American banner would wave in triumph over the proud pennon which held in the gale the boasted strength of the British Lion. They began to anticipate the return of peace, and as if to place at defiance the forms existing around them, this little band of prisoners, in the very heart of British authority, proposed the establishment of a Republican Government. They determined to regulate their affairs so long as they remained in prison, according to the pure principles of democracy. They chose from their number seven representatives, who met in a body by themselves to consult for the interests of the whole, and the principal subjects that came before them for their consideration, were such as related to the internal regulations of the prison.

One thing, among others, upon which they brought their skill of legislation to bear, was the enactment of laws concerning the preparation of their diet. This consisted of a given quantity of peas and pork a day for each one of the prisoners, who were obliged to act as their own cooks. It was very gravely presented to the body, which was called to preside over the affairs of this little community, that the preparation of their meals was a subject which demanded an immediate and serious attention. Several plans were proposed, and advocated with all the warmth of eloquence, in the presence of the people; but that which seemed to receive the highest favor was one which corresponded the most perfectly with their ideas of equality. It was that each one should act as cook in turn, beginning with those who held the lowest rank as officers, and ascending to the highest until all had been made to serve. It had been found by experience, that if the peas and pork were put on to boil at the same time, the latter, which required much less time in cooking, would be boiled to pieces before the peas would be in an eatable condition. It was therefore enacted as a solemn law, that the peas should be put over the fire first, and that after they had boiled a given length of time, the pork should also be subjected to the operation of heat. But it was further ascertained that the pork was somewhat rusty, and it was made the duty of the cook to cut this off before boiling. A failure to comply with these laws or any delinquency in the acting cook, subjected the offender to a trial and to such punishment as the people thought proper to pronounce in his case.

Under the operation of these laws their culinary affairs advanced prosperously, and not until it came to be the turn of one who had held the office of Major, was there the least opposition to the regulations that had been made. He began to plead exemption from performing the duties of cook, on account of his being a field officer. In answer to this he was reminded of the fact that he was under a Republican Government, that all were on an equality and that he could have no excuse for not performing his duty.

He therefore complied with the regulations, but it was evidently with great reluctance, and so miserably did he act his part that when that little Democracy assembled around the dinner table, their fare was in such a wretched condition that none of them could eat.

It was found that the Major had not regarded the rule about putting the peas into the kettle first, but had tumbled in peas and pork at the same time. Neither had the rust been removed from the pork, and besides, he had allowed the dinner to get burnt, so that the accusations against the Major were quite numerous, and he was immediately arraigned before the appointed tribunal. The charges were tabled and after hearing the statements on both sides, the evidence appeared to be decidedly against him, the verdict was brought in—“Guilty,” he was sentenced to be cobbed, and was accordingly laid across a bench with his face downwards, and the magistrate taking hold of one end of his shoe, proceeded to administer the given number of blows.

The Major complained bitterly of his treatment; he was so much dissatisfied that he entertained serious thoughts of rebelling against the government, and as there was no one discontented but himself, he resolved on forming an aristocracy in the midst of this nest of republicans. He nailed his blanket up between a couple of joists in the prison, and throwing himself into this, remained most of the time alone, not mingling with the common herd, and being emphatically above the majesty of the sovereign people.

While the Major was occupying his chosen quarters in his suspended blanket, removed from the bustle and turmoil of the little world below, yet not so far as to be unacquainted with what was transpiring around him, there was a plan formed by the prisoners to effect their escape by rising upon the British guard. They matured their purpose, so far as to engage some of the Canadians, who were favorable to the American cause, to furnish them with boats to conduct them across the river St. Lawrence, intending after they had gained the opposite shore, to enter the State of Vermont by the way of Lake Champlain, and thence to proceed to their several homes.

The day and hour were appointed, and the parties for attack selected—one to fall upon the sentries, another to dispatch or secure the guard. Just as they were about to put their designs into execution, the courage of one who was to act a conspicuous part, failed him, and receiving the signal to withdraw, instead of the one for attack, Van Campen and a few others with him, who were appointed to take care of the sentries, returned with chagrin to inquire into the cause of this change in their anticipated movements. They were told by a Captain White, who had been appointed to lead the other party, “that it was too hazardous and it had better be abandoned.”

This scheme was followed by another, somewhat different in its character, but more intimately connected with the Major, who still swung in his blanket. The political birthday of American freedom was drawing near, and the prisoners determined to celebrate the anniversary of their National Independence. But they were destitute of the means of observing it according to their ideas of propriety. This difficulty was removed by one of the number, who informed them that if they would provide him with some quicksilver and a few old coppers, he would give them a coin that would pass for an English shilling. A Canadian friend supplied these, and whenever their market boy went to purchase provisions, he took of the new coin to buy a small quantity of vegetables and receiving change in return, expended it for brandy, which he brought into the prison by concealing it in his basket. In this way the prisoners had collected a good sized keg full of liquor, and kept it in readiness for their anticipated holiday.

Only ten of them, Van Campen among the number, dared enter upon the plan of celebration, and these determined to carry it through, even though their imprisonment should, on this account, be attended with ten-fold rigor. The others feared the consequences of the undertaking, and declined having any part in the festivities which had been prepared for the occasion.

The Fourth of July at length came, and it was never, perhaps, hailed with more heart-felt expressions of joy, than by that small party, who, within the dark walls of a Canadian prison, hailed the feeble light that came streaming in through the iron casements as the herald of a brighter day, whispering the mild accents of hope.

This small company of avowed patriots brought forward their entertainment at an early hour, and it was not long before their joy began to expend itself in the loud and merry laugh, and the Hessian soldiers, who were that day on guard, very often sent some of their number into the upper room where the prisoners were assembled to command order. These commands becoming at length rather too frequent and troublesome, one of their number was stationed at the trap door by which their apartment was entered, with the direction to shut it upon the first man who attempted to come with order of “Silence.” Beginning soon to grow noisy, one or two soldiers came running up, and as they began to rise above the floor, the keeper slammed the door upon their heads and knocked them down the stairs. The next order that came was from the mouth of the Hessian guns, several of which were discharged up through the floor, but fortunately without injury to the prisoners.

Splinters from the fractured floor were thrown about the room at so lively a rate that the unruly prisoners began to think seriously of observing greater silence. They were therefore, for a time, quite orderly, and as night began to draw near. Van Campen proposed that they should invite the suspended Major down to their evening's entertainment. The suggestion was approved by the others, and the inquiry was made, “How shall it be done?” “In military style, of course,” replied Van Campen. Directing two of them, therefore, to sharpen their knives, and being prepared, he gave the order—“MAKE READY,—TAKE AIM,—FIRE!” As the last word was pronounced, the two who were holding their knives, applied them to the sides of the blanket, and out came the Major, head first, to join the party at the table. The Major was received with loud shouts of applause; the prison rang with acclamations, and merry cheers resounded from every quarter. But to the poor Major it proved a more serious disaster than they had anticipated. Falling upon a bench in the room one or two of his ribs were somewhat fractured, and he was taken away to the hospital to receive medical attention. It was not, however, without leaving a threat to expose all who had been the actors in this scene.

He was true to his word; on the next morning an officer came into the prison with a list of names upon a piece of paper, the first of which was Van Campen's. As the ten who had been engaged in celebrating the Fourth were called out together, the others began to congratulate themselves that they were not of the party, and as they were led out of the prison, they followed them with an anxious look, anticipating the most serious consequences. They were brought into a Court Martial of British officers, and Van Campen, being requested by the others to represent their case for them, determined if their conspiracy should have been revealed to deny it, unequivocally, since it would at once decide their fate.

When paraded before the officers, Van Campen's name was called, and upon answering, he was told that he and his party had been arraigned for misconduct in prison and that the first charge against them was for a conspiracy to destroy the British guard.

Van Campen, believing that the crisis demanded a denial of the fact, answered firmly, “It's a lie, there is not a word of truth in it.”

The British officer then proceeded to enumerate the charges consequent upon the celebration of the Fourth of July. He replied there was a little more truth in this, that himself and some of his comrades had thought it proper not to pass over their National Holiday without giving it some little attention, and they had accordingly done all that, under the circumstances, they could to keep it in remembrance. He then related the story of their celebration, the regulations they had made in their Republican Government, the manner in which the Major had been punished for not conforming to the laws, the offence he had taken, described his abode in the blanket, and in short, gave such a comic history of the whole affair, that all of the officers were thrown from their gravity as judges, and began to laugh, regarding it as a subject of the utmost merriment.

While he was engaged in the narration, a young Hessian officer, who seemed to take a deep interest in the story, came around, and stood close by Van Campen, that he might hear every word that was uttered, and when he had ended, Van Campen turned to him and inquired if he was acquainted with any of the Hessian officers taken with the army of Burgoyne, who had been stationed in Berks County, Pennsylvania. To which he answered in the affirmative. Van Campen then informed him that while an officer there, he had often invited them to dine with him, that others had paid the same attention, they being allowed the honor of a parole, and that he thought the same privilege should be allowed to the American officers.

The young officer then represented the case to his General and was informed that it would be taken into consideration, and an answer given on the next day. Without giving them any censure, therefore, the prisoners were told that they might appear before them again, and they would then be informed whether they could be allowed the privilege of a parole. Upon returning to the prison they resolved not to inform their fellows of the result of this summons, but to keep it as a secret among themselves, revealing only this—that their case would be decided on the morrow.

On the next day, when the officer came to conduct Van Campen and his comrades from the prison, they assumed the appearance of concern, and bade their companions farewell, as though they never expected to meet them again in this world. The others sympathized deeply with their fate, at the same time feeling that, they had themselves happily escaped a sentence, which they supposed would be death. Upon coming before the British officers, Van Campen and his comrades were informed that they would have the privilege of the streets of Montreal during the day, if they would consider themselves in honor bound to return to the guardhouse for lodgings at night. To this they readily agreed, and were happy in the thoughts of again breathing the open air of heaven, without receiving it through the iron grates of a prison. Thus ended this tragic affair, but it was not without chagrin that those who through fear of punishment, refused to participate in the honors paid to the hallowed day of freedom, beheld their companions who had the hardihood to commit so great an offence, permitted on this very account, to enjoy a liberty denied to themselves.

Soon after this, Van Campen and the nine who were with him on parole, were sent to the island of Orleans, five miles below Quebec, and remaining here until November, were placed on board of a vessel bound for New York, and after a dangerous voyage of five weeks, arrived in safety at their place of destination. Here a British commissary came on board of their vessel and began to inquire of the prisoners concerning the treatment they had received. All of them told in turn a very doleful story, finding much fault with their treatment and making a great variety of complaints, until he came to Van Campen, the last whom he examined. As he came up to him he said rather impatiently, “Well, sir, have you any complaints to make?”

Supposing it to be altogether useless to offer any, even though he had been treated ever so ill, he replied, “Not at present, sir; but I soon may have.”

“Ah, upon what grounds will you make your complaint?”

“Why, sir, if you don't send us on board, ten gallons of wine, a quarter of fresh beef, and a good supply of fresh bread, I shall complain of you?”

The officer took him by the hand, and shaking it heartily, replied, “If this is all, you shall have it, sir—you shall have it;” and, true to his word, he soon sent him the articles he had named. As long as the wine and beef lasted, the prisoners found no fault with their fare.

General Carleton then proposed to let them go to their own country on parole, they pledging themselves not to take up arms against His Majesty, the King, and that they would repair to whatever point or place his Generals should call them, and placing them on board of a cartel-ship, sent them up the North river to the American lines. The officer of this vessel, perceiving that they had a good supply of wine with them, began to treat them very civilly, inviting them into his own cabin, and becoming a guest with them. They here enjoyed themselves exceedingly, and having permission to sing some of their songs, they sung several which were replete with burlesque upon the British arms, and as these drew forth the loud and merry laugh, the Captain would join in with the rest, and before he placed his passengers on shore, he was so much pleased with the company of the prisoners, that he was willing himself almost to be called a rebel.

Upon coming on shore and into the society of their own countrymen, Van Campen and his fellow prisoners found themselves at some distance from their immediate friends, with scarcely a penny in their pockets to bear the expenses of a journey. They each had a blanket, however, and disposing of these, raised a little money, and with this began to proceed on foot towards their homes. In passing through New Jersey they staid over night at a public house, where the landlord requested them to leave their names before starting in the morning, stating that inquiries were often made concerning prisoners who were returning home, and that he wished to have it in his power to gratify any friend who might desire information about them.

They had been gone but about an hour, when one of the inhabitants came in, and began to inquire of the landlord, if there was any news. “None,” said he, “but the passing by of a few prisoners, who staid with me the last night.”

“Can you give me their names?”

He presented him with a list of these, and upon beholding Van Campen's, declared that he must see him, “For,” said he, “I was at Northumberland soon after one by that name was taken prisoner, and every man, woman and child was lamenting his loss, and this must be the same person; if I can be of any assistance to him, I will.” Learning that they had been gone but a short time, he mounted his horse and pursued on after them.

Upon coming in sight of the prisoners, he called to them, requesting them to halt, and as he drew near, inquired for Van Campen. Answering to his name, Van Campen stepped forward and demanded his wish.

Upon receiving from him the name of the place where he had been taken captive, the stranger informed him of his having heard of him before, and inquired if he had with him what money he wanted to bear his expenses on his way home. Van Campen replied that money was at that time a very scarce article with him, and thereupon the stranger handed him half a joe (about eight dollars), saying that it was all he had with him, and that as he had a family to support, and was expecting to remove into the vicinity of Northumberland, he might have the privilege of returning it to him again if he chose. Van Campen thanked him for his kindness, and promised to do so with interest, as he afterwards did. With this addition to their funds, the prisoners proceeded on their way with lighter hearts, and upon arriving at Princeton, the Freemasons learning their history and apprised of the fact that one or two of them belonged to their fraternity, called a meeting at which they raised funds sufficient to hire a carriage, in which they were conveyed to Philadelphia. They were a rare looking company for the elegant vehicle in which they rode and were amazed by the curiosity excited on the way by their singular appearance.

At Philadelphia Lieutenant Van Campen received his quarter's pay, procured a suit of uniform for which he exchanged his Canadian dress, and returning to Northumberland, was received by his friends with demonstrations of joy.